David

There is a weightiness about him, a lingering silence that belies the restlessness of his heart. He is a good man, honest, a devoted father, a caring minister, a loving husband. But the valley ground is mud, and each step is made with much effort and much inner struggle.

David was born on the mountain to a father who lived to be 95 and a grandfather who lived to be the same. His eyes show a deep understanding of his world – as I watch him inhale the morning mountain air, it fills not only his lungs, but his mind and spirit. They are the perpetually red-rimmed eyes of a hunter who instinctively rises in the predawn and burns the other end of the night for family. The hills speak to him, and I watch his face as he listens, wondering what the secrets are. There is a deep awe and peace in these thoughtless moments where even the thought of prayer seems a sacrilegious assertion of human will into the peace and still of God’s creation.

Like so many men of the village, a mantle holds David’s crown of manhood, obtained after killing six wild boar. It once was a symbol of great honor, reminiscing the tests that one must pass to become a warrior. In the Lukai society of old, there was a social stratification of Chief, Noble, and Commoner based on birth, with the lowers of society serving the landowners in return for housing and protection. Class status could be changed through marriage, improving or decreasing societal rank based on the choice of a spouse. There was one level of status not based on marriage or family name, however. A noble could born or bred, but a warrior earned his position through his own merit and feats of heroism. Before the majority of the Lukai converted to Christianity in the mid-1800’s, one of the requirements for warrior status was to capture the head of an enemy. As the days of warring passed, hunting remained the standard of heroism. Upon killing his sixth wild boar, a man earned the right to wear an eagle feather and the headdress adorned with the teeth of the boar. Hunters returned to a village greeted by streets lined with children seeking a tasty morsel of success.

In David’s lifetime such a culture has disappeared. He was born a hunter-warrior, but the need for the hunt disappeared as roads to the Lukai villages were built. Feeling he could better serve his people by becoming a pastor, he went to a seminary on the coast of Taiwan. While there he fell in love with a beautiful, petite Malaysian woman. Now the image of her, young and smiling, in a wedding dress hangs opposite the hunter’s headdress. As so many of the Lukai and Paiwan have, they settled in a little city in the shadow of the mountains, feeling it was best for their careers and for their children to receive a good education. Thus our paths crossed, as I was given the desk across from his wife at the hospital chaplain’s office in a neighboring town.

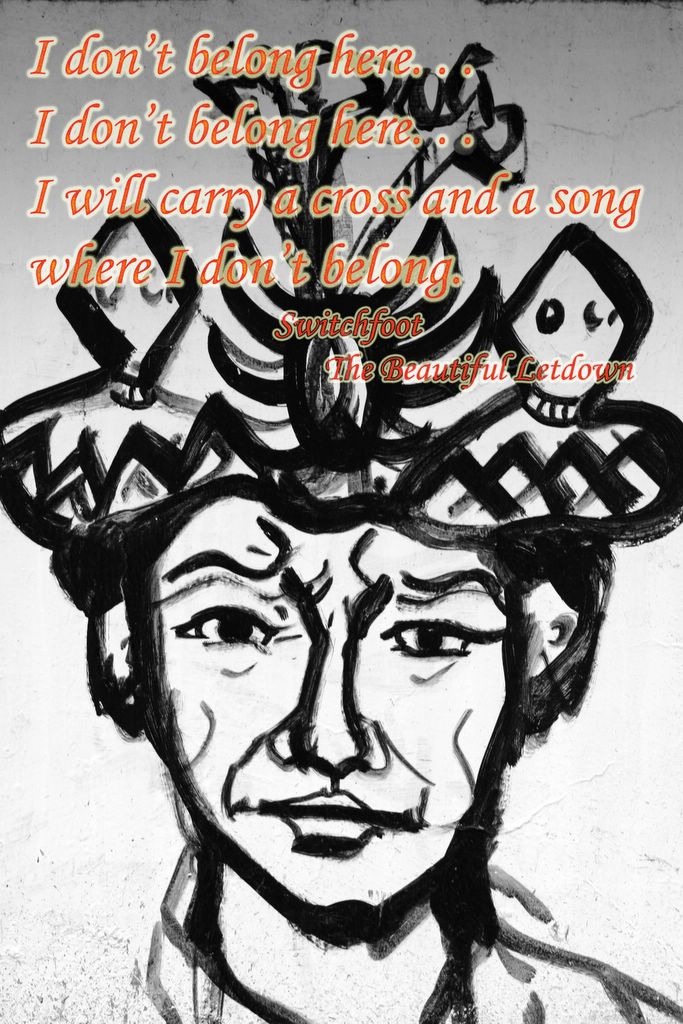

Daybreak is finishing its work, and we must begin the drive home. David recalls making the full day’s hike to Pingtung as a teenager, before the roads were built. Now, piling into his well-worn van, we can make the same drive in a little over an hour. I watch his eyes in the rearview mirror as he leaves his home behind once again, the feet intended to traverse the mountains instead pressing the brake pedal of a car headed back to an exilic home on the coastal plains. They are not bitter, nor sad. But they carry the resignation and confusion of a man who is unsure of his home.

Daybreak is finishing its work, and we must begin the drive home. David recalls making the full day’s hike to Pingtung as a teenager, before the roads were built. Now, piling into his well-worn van, we can make the same drive in a little over an hour. I watch his eyes in the rearview mirror as he leaves his home behind once again, the feet intended to traverse the mountains instead pressing the brake pedal of a car headed back to an exilic home on the coastal plains. They are not bitter, nor sad. But they carry the resignation and confusion of a man who is unsure of his home.

In David’s lifetime such a culture has disappeared. He was born a hunter-warrior, but the need for the hunt disappeared as roads to the Lukai villages were built. Feeling he could better serve his people by becoming a pastor, he went to a seminary on the coast of Taiwan. While there he fell in love with a beautiful, petite Malaysian woman. Now the image of her, young and smiling, in a wedding dress hangs opposite the hunter’s headdress. As so many of the Lukai and Paiwan have, they settled in a little city in the shadow of the mountains, feeling it was best for their careers and for their children to receive a good education. Thus our paths crossed, as I was given the desk across from his wife at the hospital chaplain’s office in a neighboring town.

Daybreak is finishing its work, and we must begin the drive home. David recalls making the full day’s hike to Pingtung as a teenager, before the roads were built. Now, piling into his well-worn van, we can make the same drive in a little over an hour. I watch his eyes in the rearview mirror as he leaves his home behind once again, the feet intended to traverse the mountains instead pressing the brake pedal of a car headed back to an exilic home on the coastal plains. They are not bitter, nor sad. But they carry the resignation and confusion of a man who is unsure of his home.

Daybreak is finishing its work, and we must begin the drive home. David recalls making the full day’s hike to Pingtung as a teenager, before the roads were built. Now, piling into his well-worn van, we can make the same drive in a little over an hour. I watch his eyes in the rearview mirror as he leaves his home behind once again, the feet intended to traverse the mountains instead pressing the brake pedal of a car headed back to an exilic home on the coastal plains. They are not bitter, nor sad. But they carry the resignation and confusion of a man who is unsure of his home.

<< Home